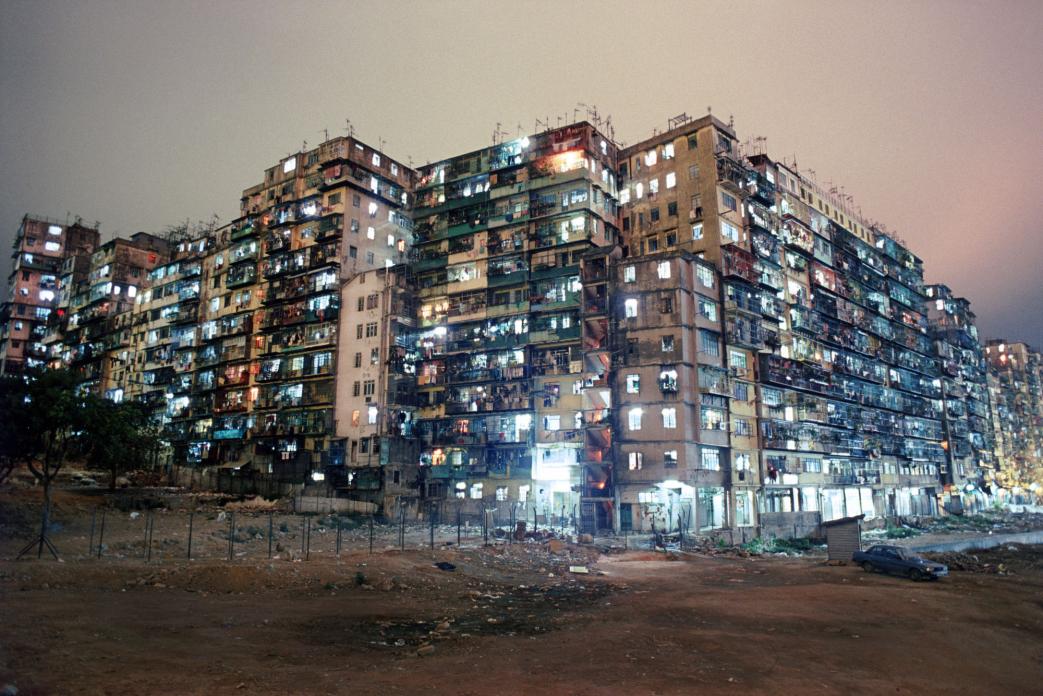

Situated north of Hong Kong there once stood the infamous densely populated Kowloon Walled City. What began as a military fort grew into a populous squatters’ village. 40, 000 people lived, worked, and crammed into 350 interconnected high-rise buildings on just 6.4 acres – all constructed without a single architect’s contribution._x000D_ _x000D_ Canadian photographer Greg Girard, in collaboration with Ian Lamboth, spent years familiarising, investigating, and documenting the ungoverned complex before it was demolished by 1994.

'I spent five years photographing and becoming familiar with the Walled City, its residents, and how it was organised. So seemingly compromised and anarchic on its surface, it actually worked and to a large extent, worked well,' said Mr Girard.

Hong Kong experienced an influx of Chinese immigrants after the Japanese occupation in World War II, leading to a lack of housing. As a response to the crisis, entrepreneurs and those with ‘squatter’s rights’ in Kowloon began to build to capitalise on the housing demand.

During the 1950s, the mega block was a lawless haven for criminals and drug users, which was run by organised crime syndicates, the Triads, until 1974. It became notorious for brothels, gambling, and cocaine and opium dens. Despite the crime, its inhabitants carried on with their lives in relative peace; and, contrary to popular belief, daily police patrols became a regular part in the city from the 1950s onwards.

Because there was no regulation or licenses enforced, it was easy to set up businesses. Rent was considerably lower compared to the rest of the city. There were a number of dubious dentists who could escape prosecution if anything went wrong with one of their patients. Doctors and other accredited professionals who emigrated from China found their practicing licenses were invalid in Hong Kong.

Food was a large part in the city’s culture. Many locals visited the dog-meat restaurants within the city before it was banned by the British.

By the late 1980s, crime rates decreased and the complex normalised but its reputation stayed till the very end.

Building codes were not enforced and so the complex was ungoverned by health and safety regulations. Dark alleyways dripped with overhanging pipes and narrow corridors mazed throughout it. A massive network of passageways on the upper levels made it possible to travel from one end of the city to the other without walking on ground level.

According to Girard, the complex had its own micro climate due to the immense amounts of tubing, wires, and open gutters. The lower levels were constantly hot, humid, and damp.

'There was never any top-down guidance or planning about how the place should be. It grew as an organic response to people's needs,' said Girard.

The only regulation enforced was that the building height not be taller than 13 or 14 stories due to the nearby Kai Tak Airport.

The quality of life and sanitary conditions were squalid and behind the rest of Hong Kong. Those living on the upper levels sought refuge on the rooftops high above the city. A befitting sanctuary, the rooftops were the only place they could escape windowless flats and breathe fresh air.

The city soon became a diplomatic crisis. It was located on Hong Kong territory, which was a British colony until 1997, but legally a Chinese military fort. The city found itself in legal purgatory as British and Chinese governments refuse to take responsibility.

Eventually both the British and Chinese found the city increasingly intolerable, despite the lower crime rates. Plans were made to demolish the city, but many residents protested against the notion and said they were happy living in the poor conditions.

The government spent $2.7 billion Hong Kong dollars (about $4.6 billion Australian dollars today) in compensation to the some 33,000 families and businesses. Some were still not satisfied and tried to stop the evacuations, which started in 1987 and ended in 1992.

Demolition of the city completed in 1994. The area where the Kowloon Walled City once stood is now Kowloon Walled City Park. Artefacts from the city, such as its South Gate entrance and three old wells, are on display. The park’s paths and pavilions were named after streets and buildings in the Walled City in remembrance of the once most densely populated place in the world.

Visit Girard’s re-release of City of Darkness for a collection of essays and more photographs of the lawless city.

Author: Dalina Nguyen

Images: courtesy of Greg Girard and others listed in Bibliography below

Bibliography

- Daily Mail. (2012). [image]. kowloon_protest 2. Retrieved July 1st, 2016, from http://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2012/05/05/article-2139914-12EF332E000005DC-237_964x616.jpg

- Imgur. (unknown). [image]. Kownloon_aerial. Retrieved July 1st, 2016, from http://imgur.com/bZkln0d

-

- SCMP. (2013). [image]. kowloon_protest. Retrieved July 1st, 2016, from http://cdn4.i-scmp.com/sites/default/files/galleries/2013/04/25/walled8.jpg

- Vice. (2014). [image]. kowloon_exterior. Retrieved July 1st, 2016, from http://assets.vice.com/content-images/contentimage/147088/Captura-de-pantalla-2014-04-07-a-la-s--18-17-26.jpg

-

- Wikipedia. (2013). [image]. Kowloon_Walled_City_1991_exterior. Retrieved July 1st, 2016, from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Kowloon_Walled_City_1991.jpg

- Wikipedia. (2013). [image]. Remnants_of_Kowloon_Walled_City's_South_Gate. Retrieved July 22nd, 2016, from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/84/Remnants_of_Kowloon_Walled_City's_South_Gate.JPG

- Wikipedia. (2013). [image]. Kowloon_walled_city_park_pagoda. Retrieved July 22nd, 2016, from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/Kowloon_Walled_City_Park_%E4%B9%9D%E9%BE%8D%E5%AF%A8%E5%9F%8E_02.jpg

- All Other Images: Greg Girard. (2014). [image]. Kowloon Walled City (book). Retrieved July 1st, 2016, from http://www.greggirard.com/work/kowloon-walled-city-(book)-13